In Part I of this series, I talked about the possibility of resolving conundrums or puzzles in your life through writing about them. I’m certainly not the first person to suggest writing about what’s on your mind. Lots of people do it through journaling, often as a daily activity. This can be a wildly successful part of your life (and help you sleep) as you “give away” the problems you’ve faced during the day by leaving them in a diary. Of course, the problems rarely disappear from reality, but the sad or scary or depressed feelings they’ve generated may well be alleviated in the writing.

Creative Journaling and Resolution

What I’d like to talk about here is taking the journaling process one step further: imagining what might have happened to make things work out all right for you and the people concerned. I suggest this because the process of inventing outcomes often leads to a better understanding of where the problem or puzzle has come from. In other words, it may “put the issue to rest” in your mind. For example, a friend of mine recently lost her husband to cancer. He had decided not to have chemo and died long before she thought he would have, had he had the treatment doctors suggested. She has berated herself for not being more persuasive with him, for not convincing him that chemo was in his best interests. Journaling has helped. But think of what would be possible for her if she decides to write further about the experience. She’d likely do a lot of research on people with cancer who refuse chemo versus those who go through it. I believe she’d gain a deeper understanding of why many refuse, and, perhaps, be able to forgive herself for not being able to keep him alive.

My Father’s Journey

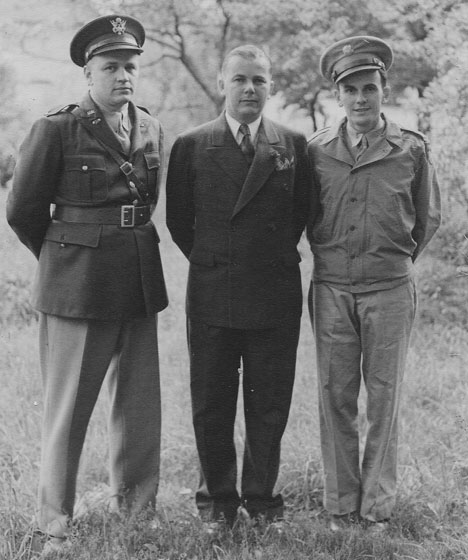

Now, certainly, she wouldn’t have to write and publish a memoir to gain such understanding. But I’ve found that unless I take a long view on a puzzle, I’ll only “solve” it superficially. The full solution comes when I’ve put myself in the shoes of my protagonist, set up the context, and explored how he/she acted that I begin to honor the decisions my model made. For example, my second novel is based on my father. He was a captain in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), Secret Intelligence Branch, during World War II. When I was growing up in the fifties, he told my brother and me heroic stories of his activities. One of them concerned how I got the name Lorelei. My mother was against giving a child a German name in 1946. My dad said it was his code name when he was behind German lines, and it had kept him safe. He wanted me to be gifted with that same safety.

I grew up with that touching story and also with the image of my father as a superhero. My brother and I agreed that we might not have had the courage to act as he did. So, in the late 1990’s, when I announced I wanted to write fiction, my brother challenged me to take my father as a model and write about his heroics. I took a few years to decide to give it a try and then spent about six months in the National Archives, carefully researching every day of my father’s time in Europe. He never was behind enemy lines. No agent ever had the code name of Lorelei. The OSS only sent agents into Germany if they were native German speakers. My father, on his exit papers from the Army, listed his proficiency in spoken German as “poor.” In fact, every story he’d told us about his OSS activities was a lie. Rationally, I understood why, as all OSS members signed a confidentiality agreement at the end of the war never to talk about their activities. Dad honored that. And lied to his family.

A Novel Inspired

I gave my brother a 34-page single-spaced report of where dad was in his year abroad (with footnotes). Our superhero had been an administrative assistant in London and then in charge of microfilming documents when he moved to the continent. The only time he was in Germany was after the German army had retreated from an area. At that point he and his team would roll in to copy documents of interest to the Allies. My information on his whereabouts came from many sources from Eisenhower’s staff to Dad’s immediate supervisors to his own reports, and included quotations from documents stating his orders. My brother told me it was all lies, that Dad had done all the things he had told us, and OSS had forged all the papers I reviewed to cover up his heroic actions. Frankly, to my mind, my brother simply couldn’t to give up his vision of a heroic father. Now me? I laughed. That idiot father of mine had so wanted to be a hero, he made up a whole different war for himself. It was an immense relief to feel he hadn’t been a superhero but a mortal.

So, I thought to myself. Why? What happened to him that he had such a need to be a hero? And how would someone with such a powerful need act in the context of the 1950’s when men were supposed to be happy to be at home with wives and children? My dad was angry at everyone. How else might he have behaved? This started my second novel The American Dream.

Exploring Life’s Puzzles

Now, think back on your own life and start asking questions:

• What episodes in your past remain unexplained? Did a friendship or marriage end in an odd or abrupt way? Were you ever refused a job or an honor without having a clue why? Has there been a rift in the family that doesn’t made sense to you?

• What characteristics or habits of important people in your life seem weird? Why did your father drink? Why did your mother hate fish and fishing? How come your sister got so much attention and you so little?

• In what puzzling contexts have you found yourself? Did you ever move residences and find yourself with the oddest neighbors? Although you were popular in high school, did you find yourself left out in college? Were there problems adjusting to the changing culture of a new company?

In Part III of this series, I’ll talk about how to take this puzzle you’ve identified to the next level. That is, how to develop the situation and people into a story with a conclusion that satisfies these conundrums from life.

To be continued. . .