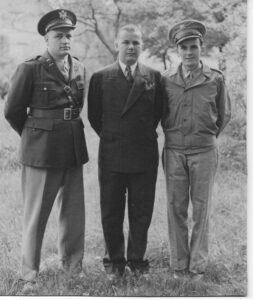

When I told my older brother (about 2010) that I was looking around for a topic to write a novel about, he said I had to write one about what our dad did in the war. Dad (Edwin Franklyn Brush, shown below with his brothers ca. 1942) had told us thrilling stories about his time in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in World War II, and I thought perhaps my brother was right. I resonated with the idea of writing a thriller about Dad’s spying exploits. I headed to the National Archives II, just outside Washington, D.C., which houses O.S.S. papers.

I spent about six months pouring over reports from the OSS concerning Secret Intelligence, my dad’s section. I started with his personnel files, reviewed his training, his London assignments, and what he was assigned on the Continent. I had heard that, at times, he was attached to the Field Photographic Unit and the Target Forces, a good start. Then I expanded to the commentary on all his OSS activities produced by each of the Army and Navy units Dad was attached to, and by General Eisenhower’s staff at the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force. It was fascinating, and the staff at the Archives were a phenomenal help. In the end, I wrote up Dad’s location and activities for every week he was abroad and sometimes had information on each weekday.

Imagine my reaction when I discovered that all the stories he had told us were a lie! For instance, he said he’d been dropped behind German lines, took the identity of a German major named Karl Ludwig Fischer, and became a liaison officer who carried messages from unit to unit. It was a perfect set-up to gain valuable information for the Allies. His code name, when reporting back to the Allies, was Lorelei. He argued with my mother to give me that name because it had kept him safe during the war and it would keep me safe. Lovely thought, except:

- OSS never sent anyone into Germany who wasn’t a native speaker. My father, himself, said at the end of the war his German was “poor.” He was certainly no native speaker.

- No OSS agent was ever code-named Lorelei.

That was just the start. Once I knew what he had done, I was certain he’d made up most of his stories. But why had he felt he needed to? Many returning soldiers simply didn’t wish to speak of their time in the war; my dad could have joined that group.

I did find an explanation that seemed to fit. At the end of the war, all OSS members signed an oath promising that they would never speak of their activities during the war. Until the time Dad died in April 1972 (when I was 25), he had kept that oath—in his own way.

I think he desperately wanted to be a hero and believed the war would give him the opportunity. But it didn’t. Before he joined OSS, he was a part of the Chemical Warfare Service of the U.S. Army. His assignment in 1942-43 was the Sun Rubber Company in Akron, Ohio. Before (and after) the war, it made rubber squeaky toys for children, like the ones in the pictures below:

His assignment was to help the company construct gas masks for children with the faces of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. Imagine the embarrassment of a man who enlisted to be a hero when he discovers he, quite literally, is assigned a “Mickey Mouse” job! It’s no wonder that, when his unit asked for “volunteers” (and he heard a rumor it was for OSS), his hand shot up.

Unfortunately, from his view, his first OSS assignment was as an administrative assistant to the director of Secret Intelligence in London. He made arrangements for others to travel, ordered supplies, and took notes at meetings. Next came the Target Forces, which went into German cities just after the Nazis left, to find persons of interest, locate important work at research facilities, and pry products from industries of interest. He was in charge of microfilming the confiscated documents. He cannot have been a satisfied man.

Next stop, Cleveland, Ohio with the war at an end. Back to teaching high school science. Even though he used the GI Bill to get a law degree, he practiced family law (after the school day ended) and made little money. He was one unhappy—and angry—man.

And that’s what he was throughout my childhood: angry. I wrote Chasing the American Dream to figure out how he might have made his way out of that anger and resolved his need to be a hero. Maybe even find contentment.

P.S. When I showed my summary of Dad’s activities to my older brother (with copies of the Archive’s materials), his response was anger. He threw the document across the room and yelled that Dad had done every one of the things he’d told us about, that OSS staff had cleverly disguised his true activities in all these papers. Dad was his hero. I, on the other hand, laughed. To me, this man had finally put his feet on the ground; he’d kept his oath. Instead of a superhero, he was like all the rest of us, someone who struggled all his life to make his American Dream come true.

Contact Lorelei to pre-order your copy of Chasing the American Dream, which is expected to hit bookstores this Fall.