As I explained in my September blog post, until he died when I was 25, I knew my father as an angry man. He came home from teaching high school many nights spewing his unhappiness. His students didn’t really want to learn; too few bothered to do the assigned homework; his principal was an idiot. As we’d pull out of the driveway on an errand, he’d notice someone left an upstairs light on and yell: “Do you think I’m made of money?” He scared me, as I was way too often the object of his anger. I kept him waiting when he wanted to leave. I “refused” to learn to drive a stick-shift car (after being rear-ended my first time out). I swore at a boy who’d taken my notebook and wouldn’t give it back. I got a B+ in English, which seemed to mean (in his mind) that I wasn’t working hard enough. I took to avoiding him, as sometimes it seemed he was just looking for someone to yell at—and I didn’t care to be that person. So, in writing Chasing the American Dream, I set out on a quest to find a very different sort of resolution for his anger than taking it out on the family.

As I explained in my September blog post, until he died when I was 25, I knew my father as an angry man. He came home from teaching high school many nights spewing his unhappiness. His students didn’t really want to learn; too few bothered to do the assigned homework; his principal was an idiot. As we’d pull out of the driveway on an errand, he’d notice someone left an upstairs light on and yell: “Do you think I’m made of money?” He scared me, as I was way too often the object of his anger. I kept him waiting when he wanted to leave. I “refused” to learn to drive a stick-shift car (after being rear-ended my first time out). I swore at a boy who’d taken my notebook and wouldn’t give it back. I got a B+ in English, which seemed to mean (in his mind) that I wasn’t working hard enough. I took to avoiding him, as sometimes it seemed he was just looking for someone to yell at—and I didn’t care to be that person. So, in writing Chasing the American Dream, I set out on a quest to find a very different sort of resolution for his anger than taking it out on the family.

The novel is set in the 1950’s, a time when many people held a traditional stereotype of manhood. Boys—and men—were told that men don’t cry, never say uncle, don’t walk away from a fight. Showing fear might be shamed. Even being vulnerable might be taken as a sign that a man is not tough enough, not really a “man.” (1)

Dr. Avram Weiss argues in Psychology Today that anger is the emotion men are most comfortable with and, really, is the only socially acceptable emotion for them. Men who are angry are seen as more powerful and more masculine (2). Jim Thornton tells us in Men’s Health that anger can be a very positive emotion, as it energizes and motivates action, triggers optimism about winning, and taps into the same brain regions associated with happiness (3). No wonder it’s so commonly shown to us!

Certainly, we all feel anger at times. Perhaps we’ve been treated unfairly or feel threatened. We may believe that others don’t respect our authority, feelings, or property. A child or co-worker may interrupt us when we’re bent on finishing a task. Maybe we’re stuck in rush hour traffic. Feeling anger is not unusual, not wrong, it’s how we feel. But is that all we feel?

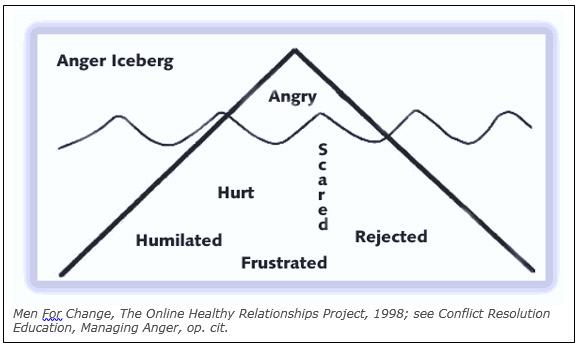

There are strong arguments that anger is a secondary emotion, the tip of the iceberg that is largely made up of other emotions such as fear, rejection, frustration, hurt, humiliation, inferiority, low self-worth, insecurity, even an inability to express feelings (4). For example, a husband gets angry with his wife for texting in his presence. Weiss (5) argues that the underlying emotion is likely to be fear, in this case fear that she likes the person she’s texting more than she enjoys talking with her spouse. I think the underlying emotion for my dad was a sense of humiliation that his jobs in the war were administrative: first helping on the home front to design gas masks for children using Disney characters; then serving overseas as a secretary for OSS’s secret intelligence branch, and finally taking microfilms of German documents. He wasn’t in the “fight;” he hadn’t been a hero.

As is fully predictable, Dad’s anger had consequences. In general, anger messes up relationships within the family, at work, and with friends (6). That was true in my avoidance of my father. In addition, the individual himself suffers. And also, frequent use of anger is related to high blood pressure, depression, anxiety, and heart disease (7). My father, as an extreme example, had his first heart attack at age 41 and died of his fifth at age 59.

So, in creating my fictional account of what might have happened to my father in the ‘50’s, I built a story around an angry, unfulfilled man who took one last stab at being the hero he’d missed being in the war. And his actions, of course, had significant consequences for his family, his work, his friendships, and most of all, for him.

-

- Gupreet Singh, Why Do Men Get Angry? https://www.welldoing.org/article/why-do-men-get-angry, September 17, 2018.

- Avrum Weiss, Ph.D., Men’s Anger Might Mask Fear. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/fear-intimacy/201809/mens-anger-might-mask-fear, September 16, 2018.

- Jim Thornton, Why Are Males So Angry? https://www.menshealth.com/health/a19529720/angry-men/, April 12, 2011.

- Conflict Resolution Education, Managing Anger, https://creducation.net/resources/anger_management/anger__a_secondary_emotion.html,1998; and Singh, op. cit.

- Weiss, op. cit.

- Seth Simons, The One Thing All Angry Men Have in Common, https://www.fatherly.com/love-money/anger-management-expert-why-men/.

- National Health Service Scotland, Why Am I So Angry, https://www.nhsinform.scot/healthy-living/mental-wellbeing/anger-management/why-am-i-so-angry, last updated 10/15/2020.